Amer Shomali

Broken Weddings, 2018

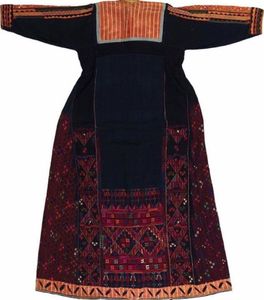

In 2017, a thobe or old Palestinian embroidered wedding dress was exhibited for sale in an Israeli auction. The dress, which had clearly never been worn, inspired Amer Shomali by bringing to mind the very short story reputed to have been written by Ernest Hemingway: “For sale: Baby shoes, never worn”. Shomali contacted the auction house for more information and was told that the seller was an Israeli who had inherited the dress from his father who had been a member of the Zionist paramilitary group Haganah. He had always claimed to have found the dress in an abandoned Arab houses during the Nakbah in 1948.

Shomali began wondering why a bride would leave behind a dress that she spent years embroidering? Was her fiancé a fighter who had been killed? Was that why she had abandoned the dress, which became a burden of past memories? Or perhaps she had been in her home and had then been killed by the man who took the dress? Whatever the answer, the wedding had never taken place.

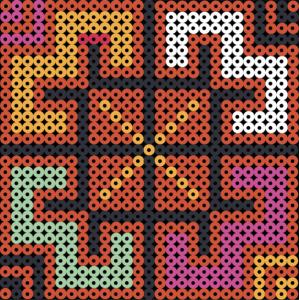

‘I reconstructed the details of dresses from several depopulated villages using balls of yarn,’ explains Shomali. ‘I replaced each stitch with a whole new ball that had never been used to embroider any piece. These were dresses that had not been embroidered, and were symbolic of broken weddings, unperformed songs, unbuilt homes, unborn children. The balls of yarn are aligned like gravestones, like bags of corpses after a disaster, like abandoned beehives, like dried wells. Threads unable to liberate themselves from their balls to say what they have to say.’

“Broken weddings, like witnesses of the possibilities of lives amputated in 1948.”

There is a very graphic element to the way that the thread balls come together to create the motifs. What role did your artistic style play in the way that you recreated the embroidery?

In most of my artworks I use only one material, which becomes is both the subject and the medium. By rearranging thousands of pieces of the same item, I change its meaning, a little bit like embroidery itself. My background as an engineer and later as graphic designer and animator forces me to keep on creating patterns and I see pixel art as a contemporary take, especially in this digital era.

What do the women, and more specifically, the embroidered chest panels, represent in the paintings from your Postcolonial Palestine series? In the works, symbols of Israeli colonialism are spotlighted in colour, nestled in the hands of women wearing embroidered dresses painted in black and white.

In this artwork I am depicting two paintings – Palestine and Harvest – by the master Sliman Mansour. In each painting, Sliman painted a Palestinian woman dressed in colourful embroidered dress. In Palestine, the woman is holding a few Jaffa oranges, and in Harvest, she is holding spikes of wheat. Those paintings made a great deal of sense in the late 1970s when they were painted, a time when Palestinian farmers were united with the land and playing a crucial role in pushing forward the production cycle. I repainted a detail of those two paintings, focusing on the hands. I replaced the oranges with bottles of Tapuzina, a type of Israeli orange juice, and replaced the wheat spikes with Israeli Berman bread. Both brands are popular among Palestinians who work in Israeli factories as cheap labour and who are the descendants of Palestinians who used to own Jaffa orange orchards and wheat fields in Palestine. They have lost their land and its produce. I then washed away the colours of the dresses, turning them into mourning blue dresses symbolizing the mourning state of Palestinian women who have lost their land, hope, and families.

‘Even though Palestinian embroidery is deeply rooted in the local context, it still speaks to a wider audience. This is the ultimate test of art – to be international while remaining locally rooted.’

To a Palestinian audience, the tatreez embroidery technique you use is easily recognizable and relatable. Do you feel that tatreez also resonates with non-Palestinian audiences?

Each culture has its own embroidery. While they differ in the techniques, colours and patterns, they all consume time and demonstrate intimacy. People from different backgrounds appreciate embroidery because it tickles a soft spot somewhere in their memories. Palestinian embroidery has another advantage as it looks like geometric abstract art, which makes it contemporary. The internationally known artist Samia Halaby, for example, is inspired by the geometrical abstraction found in the decoration of Dome of the Rock and in Palestinian embroidery. Even though Palestinian embroidery is deeply rooted in the local context, it speaks to a wider audience. This is the ultimate test of art: to be international while remaining locally rooted.

Amer Shomali is a Palestinian multidisciplinary artist, using painting, films, digital media, installations, and comics as tools to explore and interact with the sociopolitical scene in Palestine. In October 2023, he was appointed director of the Palestinian Museum in Ramallah.

Interview by Clara Wouters