Hazem Harb

Hazem Harb’s work begins by zeroing in on the unfixed, fluid areas of identity. Drawing on his evolving sense of self and situation, Harb grapples with liminal spaces, which he redefines through physical and mnemonic layers, creating a new world imagined and projected through spliced imagery, collage, and diptychs. In its geometric precision, his work can feel like an attempt to assimilate into an entirely new territory.

‘Much like my personal experience, my art exists in the interstices. It attempts to forge new connections and dialogues between seemingly disparate ideas and moments.’

In his 2020 piece, The Silk Line of Identity, Harb used a rare, late-19th century photograph featuring a posed female figure wearing the distinctive clothing then made in Bethlehem. Slicing the image and using collage techniques, he transformed this historical image into a contemporary large-scale diptych, creating a unique pattern that echoes those seen in traditional Palestinian textiles. The central figure is elevated as if a monument within the landscape, prompting contemplation of themes including value, hierarchy, and power – recurrent motifs in Harb’s imagery.

The world is slowly – perhaps too slowly – grasping how we are collectively complicit in maintaining certain liminal spaces. Can visual art, such as your signature diptychs, portray their emotional intricacies better than words?

Diptychs inherently consist of dual elements. In that, they serve as a metaphor for the liminal spaces I often find myself navigating in life. As someone living in exile, my journey through adulthood is constantly unfolding between worlds, with my mind anchored in a homeland that I cannot physically inhabit.

I am striving to carve out a lived reality in a new social world – an integration that remains elusive as my thoughts, memories, culture, and dreams reside elsewhere.

Through the incorporation of historical artefacts such as archival images, map fragments, coins, and pressed plants, my artworks bridge between the past and present. Placing these materials at the forefront in the contemporary art sphere provides them with a fresh opportunity for interpretation, while inviting viewers to reconsider their significance.

In the face of cultural erasure, my collages serve as tangible evidence of Palestinian realities, conflating diverse concepts that give rise to inquiries emerging from a third space. Through my artistic endeavours, I seek to illuminate and question, offering a nuanced perspective on complex layers of identity, displacement, and cultural preservation.

Looking at your 2020 work, The Silk Line of Identity, I feel like I’m getting a glimpse of all the global corners of your experience. The way in which your layered collage of photographs are spliced into a traditional framework seems to deconstruct ideas of containment and the fetishisation of displacement. Could you tell me more about the ideas behind this particular work?

There have been instances when international institutions and organisations wanting to address subjects such as trauma and displacement have turned to artists to perpetuate images of war and turmoil, consciously or unconsciously aligning with the standardised narratives often circulated in politics and the media. However, my artistic intent does not align with the reinforcement of these restrictive depictions. Instead, I aspire to reveal suppressed and subliminal realities that emerge from my in-depth research into the Palestinian experience. My aim is to transcend preconceived notions and offer a more nuanced understanding of the complexities involved.

Your work is also distinctive in its geometric choices of framing and mapping.

A central theme in my artistic journey has been exploring both the collective and individual narratives of the Palestinian people. This exploration manifests itself in both a literal form, drawing on archives and academic texts as the foundation of my work, and a tangible form through the innovative use of materials, particularly my fascination with Palestinian embroidery.

The intricate patterns found on traditional Palestinian dresses are uniquely tied to specific communities, enabling one to discern a woman’s village through her embroidery. These designs, which are featured in my work, encapsulate the specificity, rich heritage, and diversity within the Palestinian community. They embody centuries-old traditions and communal practices that continue to safeguard the cultural legacy of Palestinian societies facing constant threats of erasure.

The world is currently seeing images that could be among the very worst most will have ever seen. Yet these images are actually flesh, blood, buildings, trees, and seem to have shaken the West to attention. Loss reveals what people are made of. Do you think the power of such ‘images’ is that they stay in our memory, making us realise the pixels are real and real-time? It recalls your series Power Does Not Defeat Memory, first shown in Copenhagen in 2019, in which architectural shapes brought meaning to 2D topographies.

In the current landscape, focuses are even more fleeting and quickly overwhelmed as they are saturated by the constant flux of digital information. That’s why I believe that while digital media offers real-time information, it may not always be the optimal space for absorbing crucial knowledge due to the sheer volume and frequency of content.

Recognising that all media serves its purpose and brings distinct benefits, my artistic approach takes a contrary stance. It is characterised by a deliberate, time-intensive process, often involving a meticulous exploration of a minute element from historical material. Its presentation is crafted to invite contemplation, fostering an environment that encourages individuals to take the time to reflect.

In the past you’ve looked at the cactus as a persistent symbol in Arabic culture representing resilience and softness combined. You’ve referred to Edward Said’s concept of ‘Orientalism’ and the imposition of historic soft power being reshaped for conflicting agendas. I’ve been thinking about Instagram going from a site depicting visually aesthetic pleasures to the absolute polar opposite today. It’s a historical rethinking we could never have imagined. How important is the visual representation of what’s unfolding? Outside of Instagram, where do you source your day-to-day visual documentation, news, and the like?

The role of art as a means of representation and agency is undeniably crucial. In the face of conflict and oppression, art emerges as a powerful form of resistance, offering a platform to present alternative realities, document pivotal moments, unveil lesser-known truths, and challenge hegemonic forces.

When other avenues of resistance can be suppressed, art stands as a vital means of expression and defiance. The systematic suppression of Palestinian voices, whether through the destruction of olive trees or the rewriting of histories, fuels my art as a form of resistance.

My work aims to expose censored realities to a wider audience, providing insight into often-overlooked experiences. Contrasting with the spontaneity and immediacy of social media, my art, as previously discussed, is rooted in a slow and deliberate process. While social media has faced censorship and limitations, artists and art institutions have also encountered similar challenges. In an era marked by deep fakes and fake news, where traditional media can be manipulated, discerning the truth becomes challenging. As a Palestinian from Gaza, I don’t need to actively seek news or documentation of current events to feel the impact of what is happening there. The continuous flow of information from members of my community, who have experienced torture and lost loved ones due to the atrocities imposed upon the Gazan people, is a personal and painful connection that transcends mere news reports. I have personally lost loved ones in this ongoing struggle.

Certain photos and maps are used to rescue history from oblivion and make it permanent. Which other photography or photographers and maps or texts may have informed your works? I am thinking about Places and Existence (2021) and Oil and Blood: Merging (2021), which I saw you shared on Instagram last week.

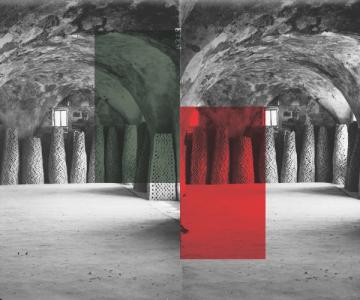

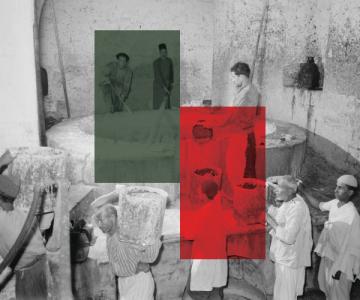

Both of those works were exhibited at the Maraya Art Centre in Sharjah in 2021. For Oil and Blood: Merging I juxtaposed photographs from a Nablus olive soap factory taken in 1934 with olive green and red Plexiglas blocks. These dual-colour panels are paired, with one consistently elevated above the other, visually connecting the factory floor to its ceiling and offering a dynamic portrayal of the workers at varying elevations. The intentional use of Plexiglas, a material commercialised in the mid 1930s as a safer alternative to traditional glass, adds a historical layer to the depiction of the soap factory, providing the artwork with a contemporary aesthetic.

This approach creates an interplay of industrial forms, revealing the architectural stacking of soap towers and showcasing the individual labour invested in crafting each component of the final Nabulsi soaps.

The series delves into the profound significance of olives for the Palestinian people, explored the intricate relationship between olive oil and blood, between a land and its people. One propels the other, their veins almost intertwined and merged into a singular essence.

In Places and Existence, an oversized sepia photographic print from 1889 features a young fallaha or female farmer, wearing a traditional thoub , meticulously positioned against the wall. A yellow neon rod precisely aligns with her head and upper body, creating a striking tension.

Poised against a burgundy-coloured backdrop reminiscent of old-master gallery walls, the woman exudes a spiritual aura, embodying the resilience, strength, and humility emblematic of the Palestinian people. While my work often deals with collective experience this woman and her embroidered dress hold connections to my personal biography and upbringing.

I’m the son of a seamstress who specialised in designing women’s dresses – and my mother, Saliha, shaped my early formative years. It was during this time that I first explored compositions of images, colours, and textures, laying the foundation for my life in art.

Hazem Harb is a visual artist born in Gaza. His practice explores his Palestinian identity, probing the challenges of diaspora, changing borders, and the repercussions of displacement. Employing a research-oriented method, he repurposes historical elements in his contemporary output. By cohesively integrating archive material into his creations, Harb affirms the ongoing presence of his community both physically and culturally, from the past to the present.

Interview by Alexandra Pereira