Taha Afefe

Haifa Started from Here, 2023

Taha Afefe is a multidisciplinary Palestinian artist based in Haifa, Israel, whose work dives into the complexities of identity, history, and language. Growing up in Haifa, he became keenly aware of the intricacies of Palestinian history’s disparate narratives, the curricular paradigms of Israeli education, and the marginalization of Arabic within predominantly Israeli spheres. Since graduating from Wizo Haifa – now NB Haifa School of Design – in visual communications, Afefe has investigated the subtle nuances of typography, and the semiotic potency of language and narrative construction. Taha’s oeuvre is distinguished by its insightful exploration of the interplay between the affirmation and dissolution of identity. His work not only contributes to society, but also becomes a more personal means of expression, reflecting the pressures he faces while grappling with his own identity. This struggle is particularly evident within the context of an environment saturated with divisive and often conflicting uses of language, and adds an intimate dimension to his creative output.

‘I live a narrative, the Palestinian narrative. It is my life, my language, everything; I live it in a country that in 1948 turned from a place our grandparents called Palestine into the state of Israel. Then there is another, different narrative that is forced upon me, via the official curriculum I was taught in school. There, I was taught according to the Zionist narrative, while at home I was raised as a Palestinian. The Zionist narrative creates a conflict within me every day. In my art, I use Arabic, Hebrew, and English typography to question and draw attention to the use of language, to the war of words, to stories and how war is embedded and reinforced through words.’

‘In my localized context, it doesn’t matter if you are the Palestinian, the Israeli, or the Western media, each has its own narrative. The interesting thing is how language is playing a huge role in building these different histories.’

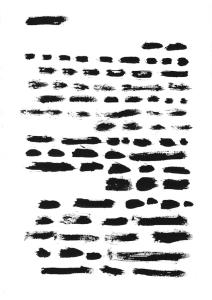

Haifa Started from Hereis composed of 1,000 A4 pages that mix the dominant languages of Hebrew, English, and Arabic reinforcing the intersecting narratives within Israel and Palestine. The pages can be randomly assembled and reassembled, drawing on the idea that reality is constructed by stories, and how the self can become lost inside language itself.

‘The work is also about understanding how a narrative is created, and how you feel that narrative and organize it within yourself. There’s always a different story.’

Taha explains ‘You feel attacked by so many narratives that in the end, you are left feeling unknown, that you almost lose your own identity,’ says Afefe. ‘You think you’re strengthening your narrative, but really, you’re losing it because you get lost in all the different languages.’

In your exploration of how language shapes our understanding of reality and is intricately tied to our identity, you highlight the complex dynamics of your region’s contemporary linguistic landscape. This blend of languages has given rise to an internal liminality, prompting a profound introspection on how you relate to yourself. Could you delve further into your personal relationship with Arabic specifically and how it factors into your overall experience?

Living as a minority, in an ethnically defined state, that considers one language to be superior and its only official language, and has enacted a nationality law to lower the citizenship status of a minority speaking another native language, your mere existence becomes determined by this reality. At home, I speak Arabic with my parents, siblings, neighbours and everybody, while at work or in the nearby town I move to the other language, the language of the majority that voted and made it lawful that my native language is discriminated against. You have to think in a different language; you have to express yourself in a different language. In our [Palestinian] story, Hebrew is perceived as the occupier’s language and this begins to form a relationship within the language itself. I have my own language, Arabic, which I feel strong and confident within, but I have to express myself day to day in a language that I don’t feel comfortable with. So I have to build my own identity through a language that’s not my own.

Hebrew is the language at colleges and universities and in most workplaces. I need to know the Hebrew language, and if I don’t speak it I cannot go anywhere. The 1948 Palestinians, not the Palestinians in the West Bank or in Gaza, but the Palestinians inside Israel were once seen by the Arab world as traitors or as the people who were normalizing the situation with Israel. With the development of social media and communications they understand us more. However, you remain stuck in between. On the one hand, you are born in the state they consider an enemy, but on the other, you are a descendant of your Arab Palestinian parents and grandparents who stood fast and remained in their homeland when Israel was established in 1948. Then there is another challenge: the Zionists and most of the leading Israeli politicians do not see Palestinians as part of their own people and express doubts regarding their loyalty. This situation alienates us both from the place we were born in, and from the Arab nation we belong to. When this occurs, something scratches the essence of your identity.

Arabic is such a rich language with millions upon millions of speakers, with fine literature and arts, but Palestinians living within Israel are disconnected from their own language and culture due to the fact that the official school system does not recognize the Palestinian narrative, history, or any related fields. We are not recognized as a national minority, therefore the rights that we have as citizens are individual rights, not collective.

Given language’s innate role and its resilience amid attempts to distort narratives and erase cultural identities, can you talk about the personal responsibility you feel for inquiring about your family’s past? How are you attempting to bridge the gap between the collective narrative and your individual identity with your art?

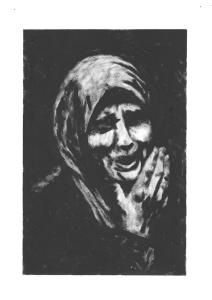

This is painful for me to explain, just as it is very difficult for my family and other families to tell their personal stories and histories to younger generations. During and after 1948, half of the Palestinian families were expelled from their villages and towns, but some families stayed, which created feelings of guilt or shame. My parents and grandparents stopped talking about what happened to our family at all. Today, I feel as if I have a responsibility to ask these questions of our past, not only for broader society, but for my family, my parents and for myself. I’m trying to tell my story as a person and as part of a collective that is striving to revive the native language and the pride of being Arab. My work is always a kind of a movement between the collective narrative, the collective memory, the collective Palestinian identity, and my own. It is a soft, gentle move in between, and has always been between the personal and the collective. I have always felt a responsibility towards my community, and bringing their message to the world. My art is for us all; it is about telling the story and the true narrative that I live and believe in.

The biggest story I am telling now is about ending the occupation. It’ s to tell people to stop the war and the occupation. But inside this message, it’ s not just about saying, end the occupation that is just a title. What I am trying to show in my art is that occupation is not only occupying a land, it is occupying identity.

‘Art and identity cannot be separated from the reality the artist experiences. Identity is challenged by this reality, so is art. If artists lose track of their identity, they may be searching for it forever.’

Born in 1991, Taha Afefe is a multidisciplinary artist based in Haifa. His work explores identity and belonging through typography and language.

Interview by Melanie Pyne